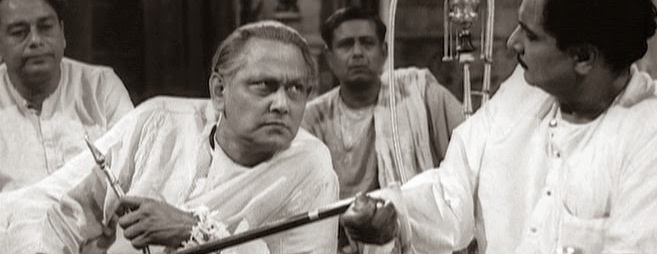

A performance in ‘The Music Room’ by Satyajit Ray

This is a weird place to start, but after watching ‘The Music Room’, I realized I have an unconscious bias against most of Indian Cinema. This realization has nothing to do with ‘The Music Room’ itself, which I expected would be great and was great. It has to do with my knowledge that Satyajit Ray was a master filmmaker on par with his peer Akira Kurosawa of Japan, and then the reputations of the two countries' film industries diverged greatly after they helped lay the foundations. Japan has produced numerous internationally acclaimed and recognized filmmakers in the decades since, whereas India has been mostly associated with Bollywood blockbusters and flashy stars. Ever since I’ve been into movies I could go to any art theater throughout the year and catch the latest critical darling of Japanese cinema, while I had to seek out the Indian cinema, if there was one, and see one of the 3 or 4 Bollywood films currently playing. Indian cinema was separated and almost acknowledged as it own populist thing in America, whereas Japanese cinema sat alongside all of the other arthouse, independent, and foreign film fare. Being the good student of cinema that I am, I discovered the name Satyajit Ray early on as an important name in world cinema history, and then not much else after him that easily came onto my radar. The impression all of that left on me I now realize is that Indian cinema as a a serious art form pretty much died after Ray in favor of populist escapism for the masses.

However, after the film I searched for the best Indian films in history and found a whole list of films and filmmakers that are a whole lot less known, even among film fans, but are regarded for the excellence and significance in shaping Indian cinema. I have a whole lot of films to check out before I can pass such a simplistic judgment on the cinema history of an entire country. As a film lover, I do not think the bias I had casts me in a good light nor am I particularly proud to share it, but I think it’s always important we acknowledge our biases and where they come from when they come to our awareness so that we ourselves, and others can learn from them. India has probably the richest and most unique artistic and cultural heritages in the whole world, so of course I want to see that represented and reflected in their films because it is my favorite art form. Maybe it is because my standards are so high that I allowed vague impressions of modern Indian blockbuster cinema to color my perceptions of over a 100 years of Indian cinema history outside of Satyajit Ray, who I accepted merely because I knew he was anointed by the critical consensus. That is sad, and I have a lot of educating myself to do by starting with my new list of must watch Indian classics.

Now let’s finally enter ‘The Music Room’ and discover what revelatory melodies Ray and his cast have to play for us. Mr. Roy is a nobleman living in an isolated crumbling mansion in the Indian countryside. His profound love of music demands he have a special music room for private concerts to be performed by the best musicians in the region for special guests at his pleasure. It is not only a way to take pleasure in his love of music, but to demonstrate for his special guests the incredible nobility, wealth, and sophistication he possesses. Unfortunately, his wealth is rapidly diminishing at the same time as his working man neighbor’s wealth is just as rapidly increasing. This threatens him so much that he feels an even stronger need to display his nobility and sophistication, which he knows his neighbor cannot match. And when his neighbor proves his sophistication by inviting the most renowned classical dancer around to his own gathering, Mr. Roy later desperately hires the same dancer while clinging on to his only advantage: his nobility, his blood, the one thing he can never lose, but also the one thing he did nothing to gain. This is what’s at the heart of Ray’s curiosity in ‘The Music Room’, old money vs. new money, the nobleman vs. the self-made man, pedigree vs. accomplishment, the past vs. the future of India.

These ideas were very much in the consciousness of India at the time as the country started to rethink some vestiges of the past, such as the caste system, and to embrace a more modern economy and culture. It’s interesting because America is one of the few countries that never really had this concept of royalty and noble blood built into its foundation, however, we have since assigned a similar status to the wealthy and politically powerful which gets passed down to the children through generations and creates a different kind of favored bloodline, and we have in turn passed that on to India as part of the modern economy and culture they are adopting. In modern India, finally, anyone can have the status of royalty, as long as they can buy it. Now that’s the American way! But back in 1950s India, poor Mahim Ganguli, the neighbor, can never buy that social status no matter how rich he becomes, and someone like Mr. Roy will not let him forget it until his dying breath. Because with his dwindling wealth, crumbling mansion, shrinking guest list, and the sudden departure of his wife and son in a terrible tragedy, his noble blood and the airs with which he carries himself are the only things he has to distinguish himself within the society. So the musical recitals and parties must go on, money be damned, until the last cent is spent, and then he knows there is only one way out, because he cannot live a second of his life undistinguished.

I really do not want to be political in my writing, but it is impossible not to picture Trump in this role. He has been exaggerating his wealth while hiding the truth behind a smokescreen of bankruptcies and investors and mysterious tax returns for years just to name the obvious, and he is now clinging so desperately to his image as a powerful, successful, and rich businessman that he will say and do anything to stay in power, to stay relevant, to stay in the media, because he knows deep down that his image is forever tarnished the second he leaves office. Love him or hate him, agree with him or don’t, but one thing is undeniable: before he ran for president his public image was almost universally positive as a successful and rich celebrity businessman (despite evidence that was freely available that this positive image was mythical already), and now after his presidency it will be at best hugely divided between positive and negative, and at worst it will in time become universally negative. That means he was willing to risk his entire legacy and that of his family just to increase his status and public image in the present, to do whatever it takes and cling on until the last moment that status and power remains in his grasp. That is what Mr. Roy is willing to do for his music room and the lifestyle it represents, because he too knows that when the money runs out and he is gone, it’s his entire family legacy that he is tarnishing, and that will be HIS legacy. So live it up while you’ve still got it, because it’s going to slip away, and soon.